It's important what the rest of the world thinks of the United States.

But it's more important that we defend ourselves against terrorists who

seek our annihilation. Much of the criticism of our efforts, both

international and domestic, is factually wrong and appears to be driven

by a partisan hostility to President Bush.

Last week the Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on Guantanamo

Bay, the U.S. military base where a $150 million facility has been built

to house detainees in the war on terrorism, individuals who might better

be described as "people who will kill Americans if given half a chance."

At the hearing, Democrats criticized the Bush Administration, alleging

that the 520 prisoners are in "legal limbo," that "there is no plan

exactly how they're going to be handled," that their "rights under the

Geneva Conventions have been violated," and that they deserve some sort

of a "trial" or they should be released. A big problem if true, but none

of it is.

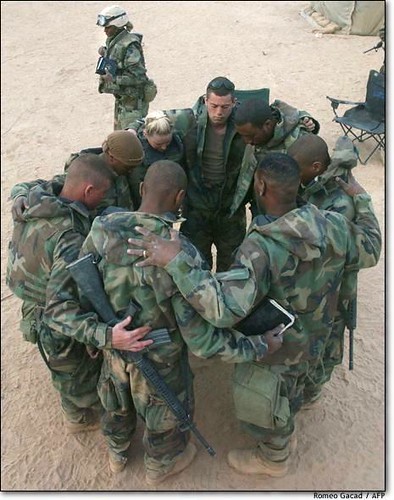

The detainees at Guantanamo are not in a legal limbo any more than any

other prisoners in any other war were in limbo when they were captured.

International law allows any nation the right to detain enemy combatants

for the duration of a conflict. The primary reason is to prevent them

from killing more Americans, and, secondarily, to gather useful

intelligence. That's why we are holding these men - they are enemy

combatants who were shooting at our troops or otherwise involved in

terrorism, and many have information that could help prevent further

attacks. We certainly never "tried" captured Nazis or Japanese POWs in

World War II (with the exception of a few leaders charged with war

crimes) although many were held for years.

The Supreme Court has since ruled that because Guantanamo is under U.S.

control, some traditional American legal procedures apply, including the

right of each detainee to have his status reviewed. After that ruling, a

special commission was established to determine whether, in fact, all of

the detainees were enemy combatants, and a number of them were released.

We know that at least a dozen went right back to fighting us, because

they were subsequently captured again on the battlefield.

Those who remain in detention - a tiny fraction of the 10,000 enemy

combatants we have picked up over the past few years - are terrorist

trainers, bomb makers, extremist recruiters and financers, bodyguards of

Osama bin Laden, would-be suicide bombers, and so forth. Because they

indiscriminately target civilians and are not fighting for another

particular country, among other reasons, these individuals do not

qualify for the protections of the Geneva Conventions. Nonetheless,

official U.S. policy is to apply Geneva standards, including access to

lawyers, Red Cross visits, and so forth. Every single detainee receives

a new review every year to determine whether he still poses a risk. That

would seem to be a reasonable standard for a country at war, and surely

a credible "plan" for "handling" their cases.

The recent flurry of partisan and international criticism of the

handling of Islamic sensibilities at Guantanamo, sparked by a

discredited Newsweek report that a copy of the Koran was flushed down a

toilet, must have Osama bin Laden rolling with laughter. None of the

critics had previously displayed much concern over the abuse of Muslims

by other Muslims, as occurs every day in Iraq. The reality is that

virtually all prisoners are better fed and cared for at Guantanamo than

they have ever been in their lives. They are certainly treated well in

comparison to those Westerners taken captive by terrorists in Iraq, who

are typically beheaded.

A handful of politicians have even raised the idea of shutting down

Guantanamo, because of its "negative symbolism." But as even vociferous

critic Sen. Pat Leahy (D-VT) has conceded, "The question isn't

Guantanamo by itself. Obviously, if we're holding people, we're going to

hold them somewhere."

Exactly. Attacking the United States should bring serious consequences,

including imprisonment, if we can catch you.

--Sen. Jon Kyl